ines/spacy-course

Advanced NLP with spaCy: A free online course

| repo name | ines/spacy-course |

| repo link | https://github.com/ines/spacy-course |

| homepage | https://course.spacy.io |

| language | Python |

| size (curr.) | 3954 kB |

| stars (curr.) | 1486 |

| created | 2019-04-15 |

| license | MIT License |

Advanced NLP with spaCy: A free online course

This repo contains both an online course, as well as a modern web framework for building online courses with interactive code, slides and multiple-choice questions. In the course, you’ll learn how to use spaCy to build advanced natural language understanding systems, using both rule-based and machine learning approaches.

I originally developed the content for DataCamp, but I wanted to make a free version so you don’t have to sign up for their service. As a weekend project, I ended up putting together my own little app to present the exercises and content in a fun and interactive way. The front-end is powered by Gatsby and Reveal.js and the back-end code execution uses Binder 💖

This course is mostly intended for self-study. Yes, you can cheat – the solutions are all in this repo, there’s no penalty for clicking “Show hints” or “Show solution”, and you can mark an exercise as done when you think it’s done.

✨ Features

- Supports slides, interactive code exercises and multiple-choice questions pretty much out-of-the-box.

- Executes code live and validates user submissions with tests functions using Jupyter kernels via Binder.

- Allows authoring content in 100% Markdown with custom elements.

- Uses the

localStorageto keep track of which exercises were already (marked as) completed. - Runs super fast thanks to Gatsby and uses all the hip and modern web stuff like React Hooks, GraphQL and service workers under the hood.

- Is open-source and published under the MIT license (code and framework) and CC BY-NC (spaCy course materials).

Related resources

- 📚 Prefer notebooks? Check out the Jupyter notebook version of this course, put together by @cristianasp.

Starter repos for your own course

- 🐍 Python:

ines/course-starter-python - 🇷 R:

ines/course-starter-r

💁 FAQ

So should I not take your DataCamp course anymore? Probably not, no.

Can I use this to build my own course? Probably, yes! If you’ve been looking for a DIY way to publish your materials, I hope that my little framework can be useful. Because so many people expressed interest in this, I put together some starter repos that you can fork and adapt.

Why the different licenses? The source of the app, UI components and Gatsby framework for building interactive courses is licensed as MIT, like pretty much all of my open-source software. The course materials themselves (slides and chapters), are licensed under CC BY-NC. This means that you can use them freely – you just can’t make money off them.

🎛 Usage & API

I mostly built this project for my own course, but it should be very easy to

fork and adapt. I made sure to strictly separate the content and the app

functionality and source. So if you want to fork the repo and create your own

course, you should only have to edit the chapters, exercises and meta.json,

update the visual assets in /static and optionally adjust the theme colours.

In theory, it should even work for languages other than Python – but I haven’t

tested this yet. You can then build your repo with

Binder and deploy it via something like

Netlify.

How it works

When building the site, Gatsby will look for .py files and make their contents

available to query via GraphQL. This lets us use the raw code within the app.

Under the hood, the app uses Binder to serve up an image

with the package dependencies, including the spaCy models. By calling into

JupyterLab, we can then execute

code using the active kernel. This lets you edit the code in the browser and see

the live results. Also see my juniper repo

for more details on the implementation.

To validate the code when the user hits “Submit”, I’m currently using a slightly

hacky trick. Since the Python code is sent back to the kernel as a string, we

can manipulate it and add tests – for example, exercise exc_01_02_01.py will

be validated using test_01_02_01.py (if available). The user code and test are

combined using a string template. At the moment, the testTemplate in the

meta.json looks like this:

from wasabi import Printer

__msg__ = Printer()

__solution__ = """${solution}"""

${solution}

${test}

try:

test()

except AssertionError as e:

__msg__.fail(e)

If present, ${solution} will be replaced with the string value of the

submitted user code. In this case, we’re inserting it twice: once as a string so

we can check whether the submission includes something, and once as the code, so

we can actually run it and check the objects it creates. ${test} is replaced

by the contents of the test file. I’m also making

wasabi’s printer available as __msg__, so

we can easily print pretty messages in the tests. Finally, the try/accept

block checks if the test function raises an AssertionError and if so, displays

the error message. This also hides the full error traceback (which can easily

leak the correct answers).

A test file could then look like this:

def test():

assert "spacy.load" in __solution__, "Are you calling spacy.load?"

assert nlp.meta["lang"] == "en", "Are you loading the correct model?"

assert nlp.meta["name"] == "core_web_sm", "Are you loading the correct model?"

assert "nlp(text)" in __solution__, "Are you processing the text correctly?"

assert "print(doc.text)" in __solution__, "Are you printing the Doc's text?"

__msg__.good(

"Well done! Now that you've practiced loading models, let's look at "

"some of their predictions."

)

With this approach, it’s not always possible to validate the input perfectly – there are too many options and we want to avoid false positives.

Running automated tests

The automated tests make sure that the provided solution code is compatible with

the test file that’s used to validate submissions. The test suite is powered by

the pytest framework and runnable test

files are generated automatically in a directory __tests__ before the test

session starts. See the conftest.py for implementation details.

# Install requirements

pip install -r binder/requirements.txt

# Run the tests (will generate the files automatically)

python -m pytest __tests__

Directory Structure

├── binder

| └── requirements.txt # Python dependency requirements for Binder

├── chapters # chapters, one Markdown file per chapter

├── exercises # code files, tests and assets for exercises

├── public # compiled site

├── slides # slides, one Markdown file per presentation

├── src # Gatsby/React source, independent from content

├── static # static assets like images, available in slides/chapters

├── meta.json # course metadata

└── theme.sass # UI theme colors and settings

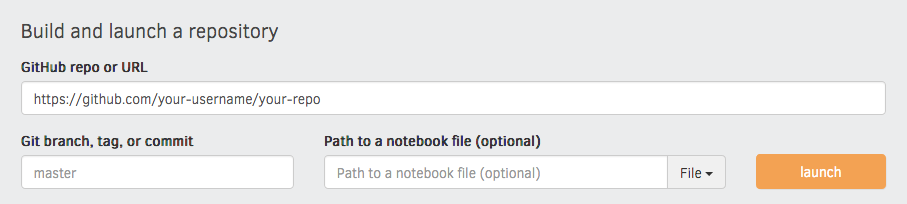

Setting up Binder

The requirements.txt in the repository defines the

packages that are installed when building it with Binder. For this course, I’m

using the source repo as the Binder repo, as it allows to keep everything in

once place. It also lets the exercises reference and load other files (e.g.

JSON), which will be copied over into the Pyt hon environment. I build the

binder from a branch binder, though, which I only update if Binder-relevant

files change. Otherwise, every update to master would trigger an image

rebuild.

You can specify the binder settings like repo, branch and kernel type in the

"juniper" section of the meta.json. I’d recommend running the very first

build via the interface on the Binder website, as this

gives you a detailed build log and feedback on whether everything worked as

expected. Enter your repository URL, click “launch” and wait for it to install

the dependencies and build the image.

Running the app

To start the local development server, install Gatsby and then all other dependencies.

npm install -g gatsby-cli # Install Gatsby globally

npm install # Install dependencies

npm run dev # Run the development server

For hosting, I recommend Netlify. It works with GitHub and Gatsby out-of-the-box.

File formats

Chapters

Chapters are placed in /chapters and are Markdown files

consisting of <exercise> components. They’ll be turned into pages, e.g.

/chapter1. In their frontmatter block at the top of the file, they need to

specify type: chapter, as well as the following meta:

---

title: The chapter title

description: The chapter description

prev: /chapter1 # exact path to previous chapter or null to not show a link

next: /chapter3 # exact path to next chapter or null to not show a link

id: 2 # unique identifier for chapter

type: chapter # important: this creates a standalone page from the chapter

---

Slides

Slides are placed in /slides and are markdown files consisting of

slide content, separated by ---. They need to specify the following

frontmatter block at the top of the file:

---

type: slides

---

The first and last slide use a special layout and will display the headline

in the center of the slide. Speaker notes (in this case, the script) can be

added at the end of a slide, prefixed by Notes:. They’ll then be shown on the

right next to the slides. Here’s an example slides file:

---

type: slide

---

# Processing pipelines

Notes: This is a slide deck about processing pipelines.

---

# Next slide

- Some bullet points here

- And another bullet point

<img src="/image.jpg" alt="An image located in /static" />

Custom Elements

When using custom elements, make sure to place a newline between the opening/closing tags and the children. Otherwise, Markdown content may not render correctly.

<exercise>

Container of a single exercise.

| Argument | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

id |

number / string | Unique exercise ID within chapter. |

title |

string | Exercise title. |

type |

string | Optional type. "slides" makes container wider and adds icon. |

| children | - | The contents of the exercise. |

<exercise id="1" title="Introduction to spaCy">

Content goes here...

</exercise>

<codeblock>

| Argument | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

id |

number / string | Unique identifier of the code exercise. |

source |

string | Name of the source file (without file extension). Defaults to exc_${id} if not set. |

solution |

string | Name of the solution file (without file extension). Defaults to solution_${id} if not set. |

test |

string | Name of the test file (without file extension). Defaults to test_${id} if not set. |

| children | string | Optional hints displayed when the user clicks “Show hints”. |

<codeblock id="02_03">

This is a hint!

</codeblock>

<slides>

Container to display slides interactively using Reveal.js and a Markdown file.

| Argument | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

source |

string | Name of slides file (without file extension). |

<slides source="chapter1_01_introduction-to-spacy">

</slides>

<choice>

Container for multiple-choice question.

| Argument | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

id |

string / number | Optional unique ID. Can be used if more than one choice question is present in one exercise. |

| children | nodes | Only <opt> components for the options. |

<choice>

<opt text="Option one">You have selected option one! This is not good.</opt>

<opt text="Option two" correct="true">Yay! </opt>

</choice>

<opt>

A multiple-choice option.

| Argument | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

text |

string | The option text to be displayed. Supports inline HTML. |

correct |

string | "true" if the option is the correct answer. |

| children | string | The text to be displayed if the option is selected (explaining why it’s correct or incorrect). |

🛣 Roadmap and todos

- Front-end tests. Also, if someone wants to port this over to TypeScript, I’d accept the PR 😛

- PDF slides. Since the app is using Reveal.js, this should be possible.

- Testing it for other languages like R. I’d be really curious to see if it

works. We’d have to adjust the

node.extensioncheck here for other files to be included via GraphQL.